About 18,000 parts go into a John Deere combine, like this one being assembled at the company’s Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois. That’s three times as many parts as you’ll find in a typical car.

Don’t be fooled by the miles of grain blurring into one endless field as you blast by on Interstate 88. 0008081131

Those stalks might all look the same to you. But farm equipment today can perceive each individual plant and know which one’s a crop, which is a weed.

A John Deere combine rattling across Gaesser Farms in Ankeny, Iowa, can recognize which type of grain is being harvested and consider the direction of the wind and the slope of the ground to orient itself with far more precision than the smartphone in your pocket can tell you where you’re standing.

GPS will place your phone’s location to within a couple of feet. But a modern combine triangulates the signal with even greater accuracy.

”We apply everything within one inch of where it’s supposed to be,” said Chris Gaesser, who farms 5,400 acres.

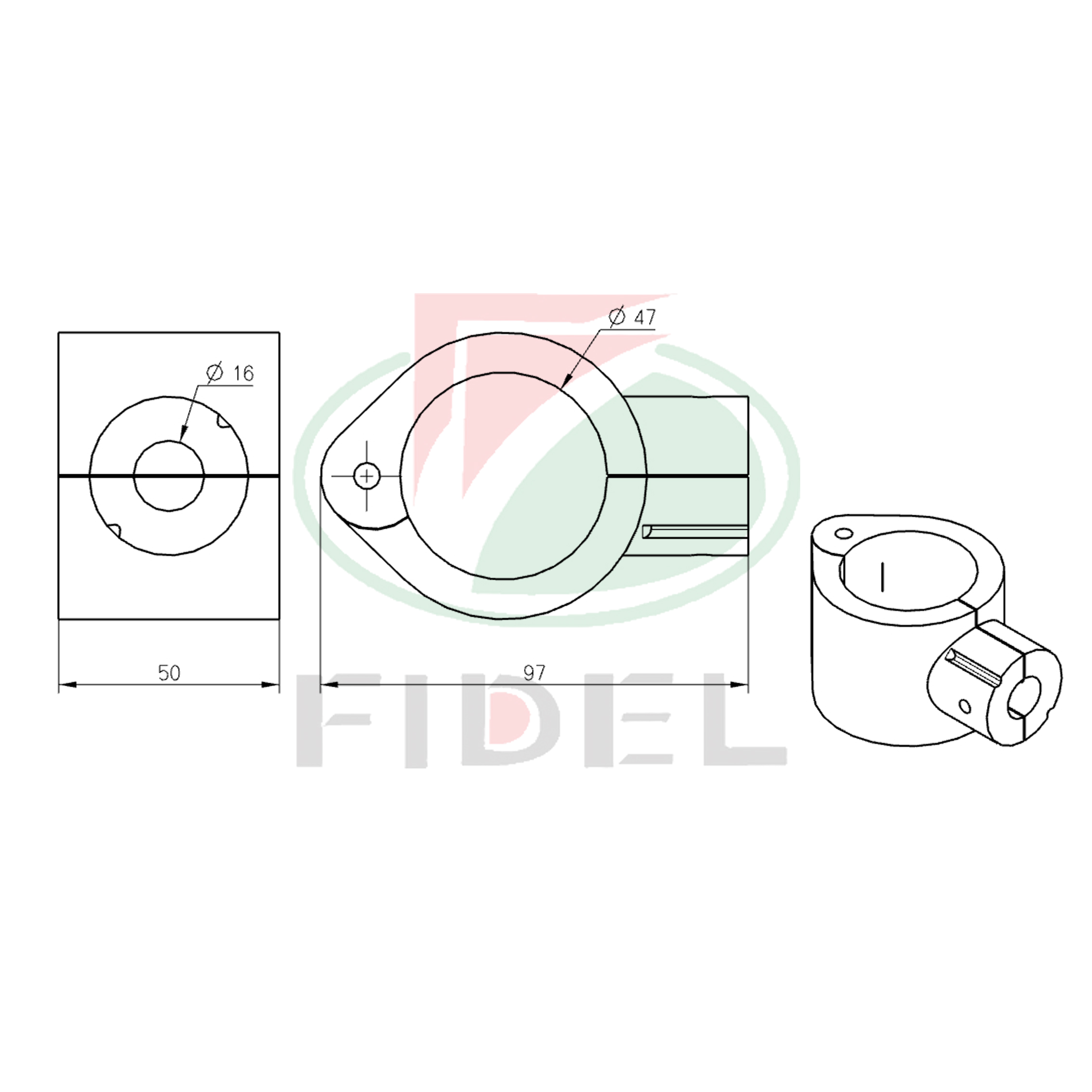

To work in the fields, each combine is paired with a “header,” a specialized front section designed to do a certain task, like these cones that separate rows of corn, seen on a combine on display at the John Deere Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois.

Such precision is necessary if you want to, say, spray herbicide on weeds but not on the dirt between them. A farm generates data faster than it generates alfalfa after a rain. Both must be handled properly to keep everything running smoothly.

If your image of a farmer is a man in overalls and a straw hat driving a tractor, daydreaming of peach cobbler, welcome to 2023. A modern farmer is more likely to be making phone calls and checking the number of “likes” on his latest #FarmTok post while the combine drives itself.

He doesn’t have much choice.

”You’re sitting in this thing 16 hours a day, many times in the fall, this is the farmer’s office,” said Jason Abbott, manager of value realization at the John Deere Harvester Works. “Think about it that way. You have to not only run your machine efficiently and productively, in many cases you have to run your business while you’re in the machine.”

City drivers are so dazzled by their shiny new hybrid vehicles’ traffic-sign recognition and 360-degree bird’s-eye view they might not realize that the same artificial intelligence revolution has revolutionized farming and the way farm equipment is manufactured.

”The tech adoption in agriculture would absolutely shock people that aren’t in the loop,” said Miles Musick, factory engineering manager at the Harvester Works, about 170 miles west of Chicago in East Moline, Illinois.

Spend a morning at the 3 million-square-foot Harvester Works, and you get a sense of how high-tech it’s all become. When a Deere factory opened in the city in 1912, it already was toward the end of the company’s first century. The company was started in Grand Detour, Illinois, in 1837 by John Deere, a Vermont blacksmith who turned an old saw blade into a self-scouring steel plow that did a better job of cutting through Illinois’ sticky black earth.

In 2023, Deere employs more software engineers than mechanical engineers. And the company avoids using the term“combines.”

”I would call them mobile sensor suites that have computational capability,” said Jahmy Hindman, Deere’s chief technology officer. “They’re continually streaming data.”

Arrive at the Harvester Works promptly at 8 a.m., and you might find yourself behind a group of men in work boots, denim, plaid flannel shirts and baseball caps who have come from Texas, Georgia, North Carolina and Mississippi. They’re there for their Gold Key tours, an almost daily ritual at Harvester Works. When it comes time to fire up the engine of a new combine for the first time, the owner is invited to turn the key.

Before that can happen, though, Harvester Works must gather together or fabricate more than 18,000 parts, which are combined to build a vehicle that can weigh 50,000 pounds. The assembly process takes about a week.

While Deere has expanded into construction equipment and recreational all-terrain vehicles, its core business rises and falls in step with the ups and downs of agriculture. In America, Deere is zigging upward. In May, Deere reported sales were up 30% in the second quarter of 2023, with record net income of $2.86 billion.

This is coming after the company was hit hard by COVID-19. At the height of the pandemic, the East Moline factory was jammed with half-built machines that couldn’t be completed because some of the necessary parts were 1,000 miles away. Some weeks, the Harvester Works had 40% absenteeism. On top of that came a five-week strike that closed the factory in the autumn of 2021.

”Supply chain was massively disrupted last year,” said Jim Leach, the factory manager in East Moline. “We had hundreds of machines that were partially complete. We still haven’t seen a return to normal yet.”

But the company is getting there, with about 2,100 employees now working three shifts.

“We’ve basically doubled our workforce in the past 24 months,” Leach said.

One way to minimize the wait for parts is to make them yourself. The Harvester Works has eight industrial Trumpf fiber-optic laser stations turning sheet metal into combine parts, chassis components and grain tank sides, then molding them on 10 press brakes — large industrial presses — in a process that is almost totally automated. The only need for human hands is to transfer the components from the lasers to the presses. The plant turns 60,000 tons of sheet steel a year into combine parts.

”We make a lot of what we need,” Musick said.

As big a challenge as making the parts is then keeping track of where they go, spread across Harvest Works’ 71 acres of floor space. Two years ago, employees were manually conducting daily inventory of which parts and aborning combines were where. Now, a large, white refrigerator-sized autonomous mobile robot purrs its way through the facility, scanning the RFID chips in various components to map the inventory down to each bin of bolts.

”We put trackers on every machine,” Musick said. “Before, we were paying people with a clipboard to write down what machine was there. As soon as you’d get done, you’d have to start over because everything was always moving.”

How to make sense of the sprawling process of combine manufacture involving thousands of parts, hundred of workers making thousands of welds, attaching rivets and tightening bolts at dozens of stations?

Perhaps the best way to envision what happens at Harvester Works is to divide combine creation into two tasks: attaching pieces together and then checking what has been put together to make sure it’s been done correctly. The second task takes twice as long as the first.

Michael Churchill (foreground) uses an impact wrench connected to the central computer system at John Deere Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois. The computer tells him when he has tightened a given bolt enough.

Assembling and checking are often done simultaneously. Michael Churchill uses an impact wrench gun containing an RFID chip that talks to Deere’s central production computer system, which knows when Churchill has tightened any given bolt enough and tells him to stop.

”We used to use guns that weren’t tied to the computer — you’d see a lot more loose hardware, missing bolts,” said Churchill, 34, who has worked at Deere for 16 years. “The computer nowadays tells you if you missed a torque, or if a bolt or a piece is missing. There’s more error-proofing the machines. You can’t go onto the next step — the computer will tell you, ‘Hey stop, you missed something.’”

Some stations build and check, others just check. A subassembly pauses so that the scanners can examine hundreds of criteria, including counting the number of threads on exposed bolts to determine if a hidden washer is in place or missing. Two years ago this check would be done by a Deere employee with a clipboard and take 20 minutes. Now it is done by a quartet of cameras mounted on tall poles and takes 1.5 seconds.

Cameras also keep track of the rolling stairs used to access parts of the machines. The line can’t move until the stairs roll back.

“What we’re trying to do inside of the factory is leverage our tech stack,” said Leach, who sees a connection between the technology building the machines and the technology harvesting the grain. ”There are cameras with algorithms that adjust machines on the fly or make recommendations to the customer to optimize settings. We’re trying to do a lot of that here.”

Like many consumers, farmers can have a fraught relationship with the technology transforming their lives.

They embrace tech because it generally works better. But the more computerized systems a combine has, the less chance there is that a farmer can fix a problem with pliers and a can of WD-40. As a result, the prices of pre-GPS combines have gone up in recent years, fed by farmers who don’t want to bother with technology.

”Some of this stuff, you lose your signal, and it just won’t work,” said Gaesser, though he also said that happens rarely and not for long.

As with smartphones, “right of repair” is a hotly debated issue among farmers, one that has led some Deere owners to sue the company, asserting that it was intentionally hampering their ability to fix the expensive combines they’d purchased.

”Deere also prohibits farmers from doing their own repairs on Deere equipment,” a posting by a group calling itself the American Economic Liberties Project said. “Farm machinery is now so technologized that even a basic repair job requires interacting with software that Deere owns.”

Deere’s stance is that it doesn’t stand in the way of farmers repairing their equipment: “John Deere supports a customer’s decision to repair their own products, utilize an independent repair service or have repairs completed by an authorized dealer. John Deere additionally provides manuals, parts and diagnostic tools to facilitate maintenance and repairs.”

A lawsuit won’t detract from the enormous respect conveyed by John Deere, whose corporate name is a synecdoche for farm life in general, the same way the Bible represents faith. “She’s a little up there, down here,” sings Jake Owen. “Puts a little King James in my John Deere.”

When Darren Bailey ran for governor last year, his campaign put out a video of his Gold Key tour, set to Joe Diffie’s anthem, “John Deere Green.”

Just painting that iconic green color consumes one wing of the Harvester Works and involves a 13-step electrocoating process of dip tanks, coating baths and robotic spray-gun arms. The parts are cleaned in solvent by being dipped in 50,000-gallon tanks, primed, dried in a furnace, then painted electrostatically — the paint particles are given a positive charge, while the metal parts are charged negatively, allowing the paint to bond to the metal in a uniform thickness and particular hardness. Each combine takes about 20 gallons of paint.

A component of a combine is lifted out of a paint bath at the John Deere Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois. The iconic shade of “John Deere Green” is applied electrostatically to create a smoother, harder finish.

Workers in space suits still need to go in afterward with handheld sprayers to touch up spots the robots can’t reach.

Harvester Works produces two “families” of combines: four models of the older S series and the new X series. One of the factors considered in the X series design was ease of assembly. Quicker manufacture means lower price. That includes trying to design away potential mistakes by, for instance, reducing the number of welds. Though welding is a task that can be done quickly by robots — the factory has 115 robotic welding arms, and half of the welds are done by robots, half by humans — a weld involves heat, which can distort metal. The last thing Deere wants to do is throw a 33-foot augur out of alignment. So fewer welds, more rivets.

Deere already is selling autonomous tractors that spray herbicides, and farmers are expecting unmanned harvesters to be operating within the next decade.

“I think that’s the direction we’re going, for sure,” Gaesser said. “Right now, everything’s bigger and quicker. I’d say within 10 years, and probably sooner than that, we’ll see smaller pieces that run all the time instead of man-operated larger pieces of equipment that run during the day.”

For now, in field and factory alike, technology goes only so far. Before each new John Deere combine leaves the East Moline Harvester Works, there is a step that does not get celebrated in the company tech stack yet is vital.

For what the company describes as “the last line of defense,” an employee lies down on a mechanic’s creeper, rolls under the new combine and checks out the underside with a flashlight.

“Despite all this technology we still have somebody making sure we’re giving the best to our customer,” Musick said.

A longer version of this story originally appeared in Crain’s Chicago Business.

03-023-864 FInished combines are lined up outside John Deere Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois. Most combines are built to order for customers, though some are made for inventory.